All clichés about U.S. pavement bard Jack Kerouac aside, chasing life along America’s roadways does provide a fine chance to get some good writing done.

However, I must admit I never could shove those clichés aside myself, not in any complete way. They’d snared my imagination amid my late teens. Their grip on my mind never lapsed until—in a sober, mature state that Wino Jack himself never quite achieved—I came to see how much fictionalizing this so-called King of the Beats deployed to gin up his narratives.

When I hit our fabled roads myself, destination unknown, as a mere lad of 22, I thought I’d launched this adventure way too late in life. That impression seems laughable now, but back then a hugely pent-up desire to seize life on my own terms felt about as volatile and incandescent as rocket fuel.

It seethed and smoked as if already ignited. Yet I remained bolted to the launch pad—jittering, shuddering, and yearning to take off.

My goals were, in no special order (each aim vied to shoulder itself to the fore): to discover the soul of America; to record my exploration and write a book about it; to have multiple romantic encounters with young ladies; to figure out where in this great nation I’d prefer to live; and to forge a new and truer personality for myself amid such wanderings.

A RAKE’S PROCESS

To a certain degree, I achieved all of these goals. Not without copious doses of sweat, angst, problem-solving and obstacle-hurdling. But I must add, a primary takeaway from my trek was one I hadn’t anticipated at all: a writing breakthrough that would nurture me in my craft for the rest of my life.

Curiously, my finding was the very same one that Kerouac so amply overused: Imagination must always be considered a vital component of any human reality. Our mentality forever colors ever iteration of experience. Objectivity is a very worthy value, and a very honorable pursuit, yet it can never be attained or claimed in an absolute or perfect way.

In the mortal words of Mr. P. Pilate, Prefect of Judea, “What is truth?”

The upshot of this axiom is that even in a case of the most serious non-fiction writing, we always should pause to evaluate it as a subset of fiction before we proceed to take it too-too seriously. Consider autobiography for example…

All right, I’ll rest my case. Now, that brief was refreshingly brief, no?

Or as Picasso so famously put it: “Everyone knows that art is not truth. Rather, it is a lie that helps us realize.”

WAY FAR OUT, MAN

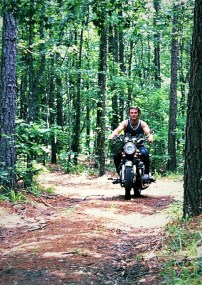

As I plotted to assault America’s asphalt assets on my motorcycle, my situation was: I’d graduated from college and saved a wee stash of cash from jobs that ranged from construction labor, to serving tables at Tallahassee’s toniest restaurant, as well as teaching multiple sessions for Poets-In-The-Schools. I might’ve fed these funds into a much safer and saner life choice—becoming a TA and tiptoeing up a primrose path into the Ivory Tower at FSU, for instance.

Instead, I had a custom pair of leather pants stitched, bought knapsacks I crammed with camping gear, and had my motorcycle—a Honda 750 modified with a Hooker Header and a Yoshimura cam—tuned into top form. I dubbed my bike “FDM,” which was short for Franklin Delano Motorcycle, since I hoped this putt would transport me to a whole new deal.

I did temporize a bit about saddling up to blow town since it meant abandoning the warm, friendly and familiar for the unknown and potentially rather harmful. A film, “Easy Rider,” released four years prior, had vividly portrayed a heap of the ugly-crazy-bad stuff could happen to a long-haired motorcyclist who dared to traipse through the wrong backwater, and so provoke the violent disgust of its locals.

FLIGHT FROM GRAVITY’S SURLY GRIP

Yet soon came a day when I steered FDM out onto a freshly built stretch of freeway dubbed the Capitol Loop. I swerved right around the sawhorses set up to keep the road barred till its official opening, and laid my body out flat on my motorcycle’s seat and gas tank. Then I twisted my throttle as far as it would go and held it tight against the stop. After I hit 128 mph, my machine could go no faster. That turned out to be my escape velocity.

The very next day, I launched into a cross-country trek that altered my life for the far better.

THE MOVING FINGER WRITES

In addition to other gear, my bike bore a tank bag that held notebooks and a battery powered tape recorder equipped with a remote microphone that I could slide up under my helmet visor. This mic sported an on/off switch that let me dictate notes as I rode. Via a blend of such audio records, scribbled notes and judicious photo-taking (hey, Kodachrome rolls were not cheap), I planned to document my journey, and thus provide myself with the requisite wherewithal for an eventual book.

Allow me to list some exploits I stuffed into that bag. I had an affair with a young lady in Mississippi, I went to Jackson and interviewed locals who’d known William Faulkner, I hung out for a week with a rambunctious, drug-dealing biker gang in Little Rock, I got bowled over by a mighty thunderstorm in the Ozarks, I camped out with a squad of ethereal hippies in Texas, I had an affair with a young lady in New Mexico, I reconnected with my best friend from our seminary days at his cabin in Cedar Crest, and I spent two weeks at a mystic commune called Lama Foundation near Questa.

ADDITION BY SUBTRACTION

Then, a disaster unfolded. Finding myself lacking more reasonable spots to spend a certain night, I elected to unroll my sleeping bag in a rough patch of desert located just under the outskirts of Santa Fe.

I found I’d chosen poorly. Not only was the ground under me hard and uneven, a distant adobe had a junkyard dog who somehow grew aware of my presence. My lack of access to bathing for many days might’ve had something to do with it… Anyhow, this grandiloquent mutt barked all night long. By the time sunrise nudged me the rest of the way out of my sleepless stupor, I felt groggy and grumpy. My situational awareness was about as keen as a butter knife that Click & Clack had used as a shop screwdriver.

Hence, I packed up in a shambling, haphazard fashion. My main aim at that moment was sussing out a roadside diner ASAP where I might refuel on breakfast and coffee. Only after I’d been swatted into full consciousness by a half-dozen cups of bitter brew and gone back out to my bike in the diner’s parking lot did I realize my precious pack crammed full of notes and recordings had not been properly secured. And it was gone.

To say I was aghast would be a grievous understatement. Since I felt quite agog, too.

SPEAK, MEMORY

I retraced my circuitous route back to the site. My pack was nowhere to be seen. Perhaps someone had trekked out there to see what on earth the dog had been barking at, then snagged it.

Hey, good luck making sense of my scribbles, I thought.

Welp, there’s only so much hand-wringing one can do without unscrewing your hands from your wrists, and I had no wish to die of aggravated RSI. What I did hope to do was write a book—and that aim seemed to remain unrelenting. I reckoned that my sole option left was to attempt to rewrite all of my notes from memory.

A ray of hope was bestowed by my friend in Cedar Crest. He was moving out of his cabin; but he had paid up its rent through the end of the month. If I moved in, I could become abbot and sole monk of a writing hermitage for two solid weeks.

I scored a stack of legal pads in Albuquerque and a sack of food staples, then scooted on into this remote mountain residence. Each day for a fortnight, I cast my mind back into my recent ramble, then proceeded to scribble about it for all the sunlit hours. (Electricity had been switched off, so my nights were long and dedicated to slumber.)

That’s when the first elements of fiction began to creep into my cross-country narrative.

It wasn’t so much that I sought to embellish what had actually happened—to me, the trip seemed entertaining on its own terms. However, I discovered that a certain narrative arc made my tale more compelling as a read. Such an arc was apparently best created by speeding up some timelines and slowing others, combining some characters while subtracting others, and so on.

I wasn’t lying, exactly, or so I thought. I’d merely begun to teach myself the dynamics of storytelling. This analysis was one I repeated to myself often while I filled the pages of the pads.

TO THUMB A LIFT FROM THE DHARMA BUM

In this manner I finally came to understand good ol’ Wandering Jack’s underlying game. And I also grasped why he’d been honest enough to call his books novels, not diaries. The actual events experienced by himself and all the other Beats constituted mere grist for his literary mill. What came out the other end of his process was jazzed-up contemporary myth.

He wasn’t using his word-flour to make quotidian bread, but to bake some holiday cakes.

I realized then that great stories can never be mere heaps of notes. However, they might be those very same notes, rigorously shaped. As well as trimmed, colored, rearranged, bolstered and invigorated by invention.

After I reached California, I spent seven more years, off and on, continuing to shape my narrative of the cross-country motorcycle trek, until it grew fit to see print in the hands of Island Press as my first published novel, “The Search for Goodbye-To-Rains.”

BRINGING VIGOR TO RIGOR

This process grew even more fascinating after I began to apply it to journalism, since that profession can enforce severe sanctions for dubious dabbling in untruth. If you ever hope to work as a reporter at any level, you should never try to spice your stories with falsehood—that can truly come back to haunt, then utterly ruin, your whole career.

My solution there was to wildly over-research every single topic I ever reported on, then contemplate this mass of material until a glowing storyline began to emerge. Reality did contain natural storylines, I found. You just had to mine a ton of ore before you could refine it and weave a golden thread.

Such notions became the quintessential harvest of my long-ago trek.

A call of the open road had tugged on me just as the mythical Sirens had once summoned Ulysses. But unlike that highly sagacious hero, I did not lash myself to a ship’s mast so that I could hear and appreciate their seductive allure without being able to respond.

Instead, I dove right into the heaving sea and swam to them. And I must laugh now as I realize that, decades on, I swim toward them still…

Because the sirens are not personages, nor goddesses, they are not even threats. They merely represent that essential unknown, something lying the opposite way from home. They are what may happen next, when you leave the familiar behind.